Länkbyggen för WordPress Länkbyggen är en viktig del av att förbättra synligheten för en WordPress-webbplats. Genom att skapa kvalitativa länkar till webbplatsen kan man öka

Introduktion till lyxiga sängkläder till billiga priser Att upptäcka sängkläder som förenar känslan av lyx med fördelaktiga priser kan ofta verka som en svårighetsgrad. När

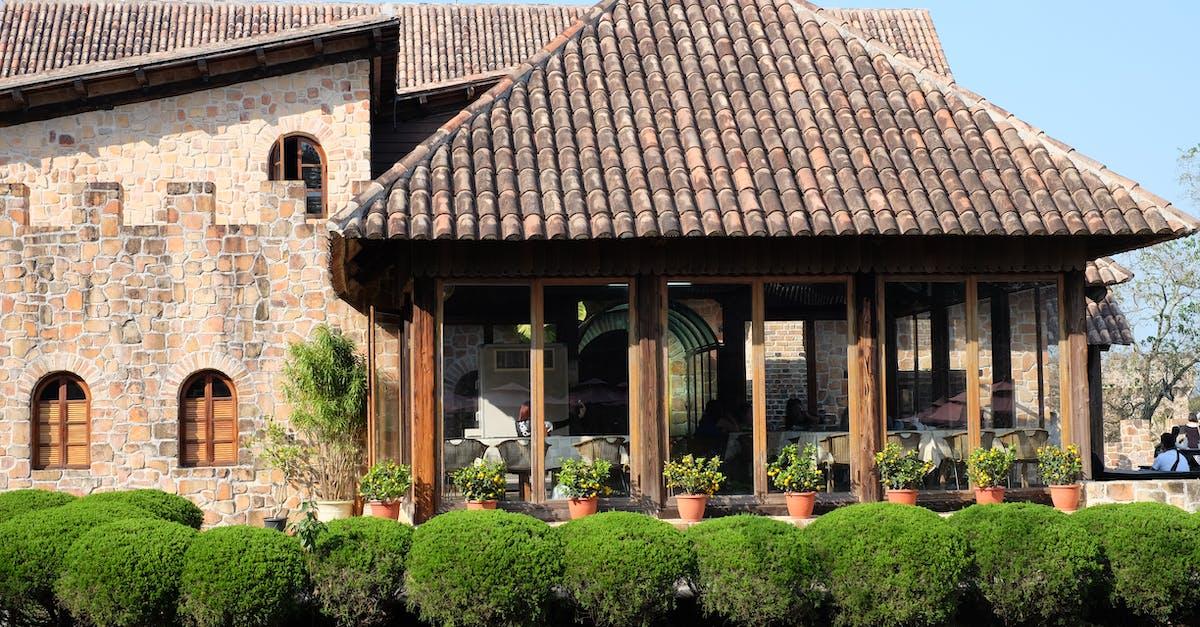

Takvård är en viktig aspekt av fastighetsunderhåll som ofta förbises. Ett välunderhållet tak spelar en avgörande roll för att skydda byggnadens struktur och dess invånare

Radon, en osynlig och luktfri gas som naturligt bildas i marken, utgör en potentiell hälsorisk som ökar under den kallare årstiden. Det är nu, när

Rökning är en av de största orsakerna till förtida död i världen. Men rökning behöver inte bara betyda cigaretter. Det finns också alternativ som snus

Slutbesiktning: En Viktig Process för Ditt Hemköp Att köpa ett hem är en av de största investeringarna de flesta av oss gör under våra liv.

Hemlarm har blivit en integrerad del av många människors liv och hem över hela världen. Utvecklingen av hemlarmmarknaden har varit en resa fylld av innovationer

Hela livet har vi lärt oss att sex är tabu och något man inte pratar öppet om. Men vet du vad? Det är helt normalt

Pagerank Vad är sidrankning? Men alla länkar är inte lika mycket värda. Länkar från högkvalitativa, relevanta webbplatser väger tyngre än länkar från lågkvalitativa webbplatser, och

En välbesiktigad arbetsplats är grundläggande för att upprätthålla en säker och effektiv arbetsmiljö. Genom att regelbundet inspektera och besikta arbetsplatsen kan du identifiera och hantera